Some years after Mortimer Menpes made his first journeys to Japan and brought a Western sensibility to an Eastern country, another artist was making the same journey in reverse. Yoshio Markino (Heiji Makino as he was born, in 1869) sailed from Yokohama to San Francisco at the age of 24. In 1897 he travelled to London where he stayed for more than forty years, bringing the artistic sensibility of Japan to his new home.

Markino lived in various parts of London including Greenwich, New Cross, Kensal Rise, Norwood and Brixton. But he found his longest lasting home in Kensington and Chelsea.

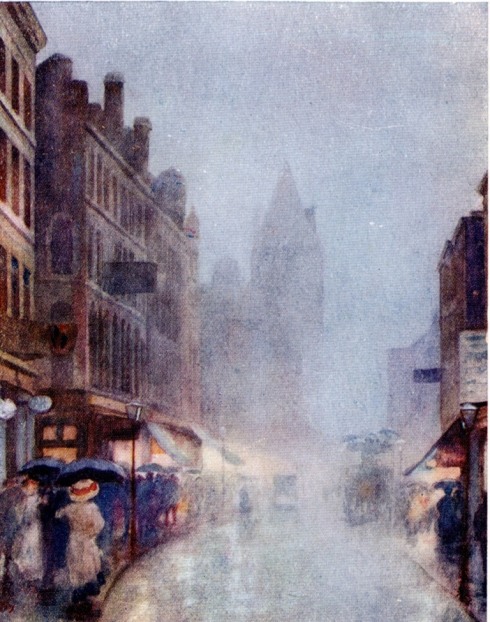

He painted the city in many moods but his preference seemed to be for overcast days, for night time and above all for fog. London in mist is far above my own ideal….the colour and its effect are most wonderful. I think London without mists would be like a bride without a trousseau….The London mist attracts me so that I do not feel I could live any other place but London.

He was sometimes called the painter of fog.

Some of the figures in his pictures look lost and lonely as if he was anticipating the night time urban views of Edward Hopper. Here is a view of his lodging house in Sydney Street.

The monochrome view makes the street look grim and cold. But there were bright lights in the misty places as in this picture of Earls Court Station.

Look at the bright clothes of the two women in the foreground, travelling to or from a theatre or the nearby exhibition centre:

There is that Japanese love of water too. The wet pavement reflects everything as if the whole city was built on a lake.

“A wet day in Sloane Square”

He did venture out in daylight too but as he says December is my favourite month in London.

Cale Street, quite close to his lodging house, perhaps looking out of the window.

There were some summer and autumn days, never entirely without the hint of mist.

A woman sits reading in Kensington Gardens. A little further south there were crowds in Brompton Road outside the museums Markino admired.

But it was the gloom he loved best, the glimpses of people entering or leaving brightly lit interiors setting out on a night time journey.

Here at Brompton Oratory, or below at the Carlton Hotel.

Markino wrote several books about his life in London. He experienced hardship and illness before he could make a comfortable living as a freelance artist and writer but never lost his commitment to his adopted home. At one point he worked for a stonemason in Norwood designing angels for memorials in the nearby cemetery. The stonemason regretfully let him go because his angels were too feminine – “more like ballet girls than angels”.

Perhaps the feeling of being a stranger gives his pictures that air of lonely detachment. I was pleased to find this one in My Recollections and Reflections (1913).

Thistle Grove with its Narnian lamposts which bring back memories of William Cowen the water colour artist who painted that area nearly seventy years before. It’s difficult to be sure whether this view is looking north or south. Because of the wall I’m leaning towards the Fulham Road end. Not so far from this scene:

The tall grimy buildings, the distant tower of St Stephen’s hospital, the shadows, the damp, the mist and amid the gloom the lights of shops and the brightness of the people living in the dark city.

Postscript

I had only been vaguely aware of Markino when I was looking for something to follow up last week’s post on Menpes. And this, if you don’t mind me saying, is the value of special collections in libraries, in our case of biographies and books about London. I found a great many pictures by Markino in his memoirs and his collaborations with other writers. The quotations come from the introductory essay in The Colour of London.

Like Mortimer Menpes we may come back to Yushio Markino.

A Japanese artist in London (1912)

My recollections and reflections (1913)

The colour of London (with W J Loftie) (1907)

Yoshio Markino: a Japanese artist in Edwardian London (1995). By Sammy I. Tsunematsu.

September 19th, 2013 at 1:17 am

Thank you! These are amazing. Another artist to study.

Sent from my HTC EVO 4G LTE exclusively from Sprint

December 18th, 2013 at 10:22 am

[…] https://rbkclocalstudies.wordpress.com/2013/09/19/the-artist-in-the-mirror-world-yoshio-markino/ […]

October 8th, 2014 at 10:27 pm

I just finished reading Markino’s autobiography ‘A Japanese Artist in London’, and immediately went looking for more information on him. Great to see such interesting writing about him as well as a collection of his paintings – there’s something about this artist and his style of both writing and painting that makes him incredibly endearing to me.

Thanks for the read.

June 22nd, 2015 at 4:43 pm

Dave, I came across this in Arthur Ransome’s Bohemia in London (1907). I’m pretty sure it refers to the same coffee-stall as is depicted in the first Markino painting on this page, which must once have stood on the corner of Battersea Bridge and the embankment. Ransome and Yoshio are known to have been close friends.

“I had hesitated before coming fairly into Bohemia, and lived for some time in the house of relations a little way out of London, spending all my days in town, often, after a talking party in a Bloomsbury flat or a Fleet Street tavern, missing the last train out at night and being compelled to walk home in the early morning. Would I were as ready for such walks now. Why then, for the sake of one more half hour of laugh and talk and song, the miles of lonely trudge seemed nothing, and all the roads were lit with lamps of poetry and laughter. Down Whitehall I would walk to Westminster, where I would sometimes turn into a little side street in the island of quiet that lies behind the Abbey, and glance at the windows of a house where a poet lived whose works were often in my pocket, to see if the great man were yet abed, and, if the light still glowed behind the blind, to wait a little in the roadway, and dream of the rich talk that might be passing, or picture him at work, or reading, or perhaps turning over the old prints I knew he loved.

Then on, along the Embankment, past the grey mass of the Tate Gallery, past the bridges, looking out over the broad river, now silver speckled in the moonlight, now dark, with bright shafts of light across the water and sparks of red and green from the lanterns on the boats. When a tug, with a train of barges, swept from under a bridge and brought me the invariable, unaccountable shiver with the cold noise of the waters parted by her bows, I would lean on the parapet and watch, and catch a sight of a dark figure silent upon her, and wonder what it would be like to spend all my days eternally passing up and down the river, seeing ships and men, and knowing no hours but the tides, until her lights would vanish round a bend, and leave the river as before, moving on past the still lamps on either side.

I would walk on past Chelsea Bridge, under the trees of Cheyne Walk, thinking, with heart uplifted by the unusual wine, and my own youth, of the great men who had lived there, and wondering if Don Saltero’s still knew the ghosts of Addison and Steele and then I would laugh at myself, and sing a snatch of a song that the evening had brought me, or perhaps be led suddenly to simple matters by the sight of the bright glow of light about the coffee-stall, for whose sake I came this way, instead of crossing the river by Westminster or Vauxhall Bridge.

There is something gypsyish about coffeestalls, something very delightful. Since those days I have known many: there is one by Kensington Church, where I have often bought a cup of coffee in the morning hours, to drink on the paupers’ bench along the railings; there is another by Notting Hill Gate, and another in Sloane Square, where we used to take late suppers after plays at the Court Theatre; but there is none I have loved so well as this small untidy box on the Embankment. That was a joyous night when for the first time the keeper of the stall recognised my face and honoured me with talk as a regular customer. More famous men have seldom made me prouder. It meant something, this vanity of being able to add “Evening, Bill!” to my order for coffee and cake. Coffee and cake cost a penny each and are very good. The coffee is not too hot to drink, and the cake would satisfy an ogre. I used to spend a happy twenty minutes among the loafers by the stall. There were several soldiers sometimes, and one or two untidy women, and almost every night a very small, very old man with a broad shoulder to him, and a kindly eye. The younger men chaffed him, and the women would laughingly offer to kiss him, but the older men, who knew his history, were gentler, and often paid for his cake and coffee, or gave him the luxury of a hard-boiled egg. He had once owned half the boats on the reach, and been a boxer in his day. I believe now that he is dead. There were others, too, and one, with long black hair and very large eyes set wide apart, attracted me strangely, as he stood there, laughing and talking scornfully and freely with the rest. One evening he walked over the bridge after leaving the stall, and I, eager to know him, left my coffee untasted, and caught him up, and said something or other, to which he replied. He adjusted his strides to mine, and walked on with me towards Clapham. Presently I told him my name and asked for his. He stopped under a lamppost and looked at me. “I am an artist,” said he,” who does not paint, and a famous man without a name.” Then, angry perhaps at my puzzled young face, he swung off without saying good-night into one of the side streets. I have often wondered who and what he was, and have laughed a little sadly to think how characteristic he was of the life I was to learn. How many artists there are who do not paint; how many a man without a name, famous and great within his own four walls! He avoided me after that, and I was too shy ever to question him again.”

June 22nd, 2015 at 9:24 pm

Chris

Yes, sounds like the place.It’s a great passage. I quoted from the same book in my second post about Markino. He comes across as a bit of a cool dude, rolling a cigarette and smiling enigmatically. Ransome’s bohemia seems rather like all the others.

Dave

July 25th, 2015 at 4:55 pm

Hello, do you by any chance know who holds the copyright to Markino’s paintings? I’m trying to clear copyright to one of his images and can’t seem to find any information about this.

Thank you!

July 26th, 2015 at 12:36 am

Veronica

I’m afraid I have no idea. I believe a great many of his pictures owned by a single collector were lost in a fire. there is an expensive art book at: http://www.amazon.co.uk/Edwardian-London-Through-Japanese-Eyes/dp/9004220399/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1437870793&sr=8-1&keywords=yoshio+markino which might be useful in that respect. All the pictures on my blog posts come from old books in our collection.

Dave

September 14th, 2015 at 4:45 pm

I have a charcoal drawing signed by a japanese person who was interned in Canada during 1943. A printed name on the drawing by the artist reads Yoshio Maedo (hard to read) and correspondence relating to the charcoal lists the artist to be Yoshio Markino. The drawing was given to one of the internment camp officers by the Japanese person as a show of appreciation for a night out at the movies.

I can find no reference that the Yoshio named here was ever intered in Canada during the WWII … is there any possibility this japanese person/artist and Yoshio could be one and the same.

Thanking you in advance for any response.

September 28th, 2015 at 4:23 pm

Sorry for the delay in replying. I had to find the right book, which was Sammy Tsunematsu’s Yoshio Markino: a Japanese Artist in Edwardian London. Writing about Markino’s final days in London he says that Markino left for Japan in 1942, arriving in Yokohama on September 29th. During the war he visited Korea and China – he was in Peking for part of 1943. After the war he lived in reduced circumstances and never fulfilled his ambition of returning to London.There’s nothing to say he was ever interned in Canada.

Dave

October 19th, 2015 at 8:02 pm

[…] do justice to the handful of illustrations. Some much better online versions are available at The Library Time Machine (and more). They seem to me to be much more European in style than Chiang, but also with an […]

October 18th, 2016 at 10:11 am

[…] Japanese painter and author, born on January 26, 1870 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yoshio_Markino https://rbkclocalstudies.wordpress.com/2013/09/19/the-artist-in-the-mirror-world-yoshio-markino/ […]

January 21st, 2017 at 8:14 pm

Mr. Walker,

I read your post with interest. Do you know my book on Markino?:

EDWARDIAN LONDON THROUGH JAPANESE EYES: THE ART AND WRITING OF YOSHIO MARKINO (Brill, 2011).

Bill Rodner

January 23rd, 2017 at 11:04 am

Mr Rodner

Yes I’ve seen your book on Amazon and other sites and have been very keen to read it, but it’s a bit beyond my price range.

Dave

January 24th, 2017 at 12:55 am

Dave,

Yeah, I know it is pricey. But it is filled with pictures. Perhaps you library can order a copy? It may interest you to know that I did some research in the local history section of the Kensington Library for the book. They had some interesting things on Earl’s Court in the Edwardian period.

Best,

BIll

On Mon, Jan 23, 2017 at 6:05 AM, The Library Time Machine wrote:

> Dave Walker commented: “Mr Rodner Yes I’ve seen your book on Amazon and > other sites and have been very keen to read it, but it’s a bit beyond my > price range. Dave” >

October 18th, 2017 at 6:12 am

[…] Japanese painter and author, born on January 26, 1870 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yoshio_Markino https://rbkclocalstudies.wordpress.com/2013/09/19/the-artist-in-the-mirror-world-yoshio-markino/ […]

May 21st, 2019 at 7:28 pm

Reblogged this on A seven's perspective and commented:

Japanese love of water. A painter of fog who loved our weather for the very reasons we sometimes grumble about it. Beautiful paintings.

May 21st, 2019 at 7:36 pm

Beautiful paintings, thank you. I wonder have you written anything on Van Gogh and Japan? I read recently that a grasshopper was found in one of his paintings that was probably placed there, it made me think of this https://aeon.co/essays/japanese-culture-conquered-the-human-fear-of-creepy-crawlies I wonder also why you call it the mirror world? Thank you!

June 15th, 2019 at 6:10 pm

Fascinating article on insects. My interest in Markino stems from his connection with Chelsea, which also took me to Mortimer Menpes, another Chelsea resident with an interest in Japan (see this post: https://rbkclocalstudies.wordpress.com/2013/09/12/mortimer-menpes-his-own-private-japan/ ) The “mirror world” is taken from William Gibson’s novel Pattern Recognition and describes an American’s feelings about comming to London and finding the way of life subtly different from her home life in New York. This seemed akin to Markino’s outsider view of London expressed in his pictures and writings.

Dave