Local Studies collections quite often contain water colour paintings by local residents. We’re all familiar with that trope of historical fiction and TV drama, the accomplished young lady who paints pictures of her neighbourhood. Mrs Elizabeth Bach Gladstone is one of those. Now we’ve seen quite a few amateur water colorists on the blog: Marianne (or Mary Ann) Rush, Louisa Goldsmid, the un-named artist of the Red Portfolio, and a few professionals: E. Hosmer Shepherd, William Cowen, Yoshio Markino. Some of them are talented, some of them are competent, some of them are a bit weird.

Elizabeth Bach Gladstone was born in 1858 and spent her young life in Kensington before her marriage to Henri Bach in 1896 and subsequently moving to France. She was the daughter of Professor John Hall Gladstone and the younger sister of Florence Gladstone, the author of Notting Hill in Bygone Times, the first history of the Notting Hill area. Her other sister was Margaret Gladstone the wife of the Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald. Margaret also did water colours but our collection has 67 paintings donated to the Library in 1933 by Madame Bach Gladstone (as it says on the card I’m just looking at).

I was probably always going to feature some of these works here at some stage but I was reminded of Elizabeth by this picture, which connects with the recent posts about Slaters and the Royal Palace Hotel.

This is a view looking south at Kensington High Street from Palace Green Avenue. On the right is Palace Avenue Lodge, and visible through the gateway, number 1 Kensington High Street (about which I’ve written already).

This area, taking in the vicinity on both sides of Kensington Church Street, was Elizabeth’s patch, and she painted this picturein 1893 when the Royal Place Hotel was newly built.

The picture below looks down Kensington Church Street.

The writing on the back of the mount (probably not Elizabeth’s) identifies the George Inn and the roof of the Carmelite Monastery but doesn’t say anything about the spire on the left. You’d assume it was St Mary Abbots Church.

Here is a better view from 1888.

The pleasure of these sparsely populated water colours is their tranquillity. The busy life of urban Kensington becomes peaceful so this dusty street becomes as quiet as a cathedral precinct.

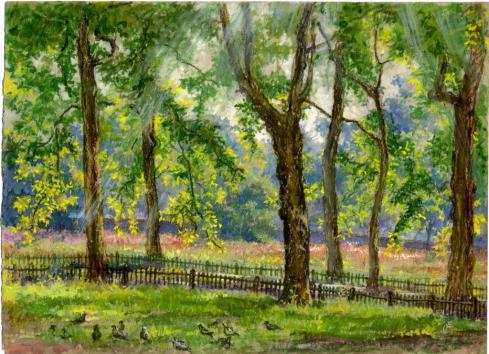

The garden below could be in a small town.

The spire in the picture though is not Kensington’s best known church, and the house is not its vicarage.

They both belong to this church, a favourite of Elizabeth’s.

St Paul’s, Vicarage Gate, briefly seen in a photograph in this post. (St Paul’s was damaged during WW2 and subsequently demolished.)

Elizabeth looks inside.

Another feature of amateur water colour painters is the figures. Not quite right in this one but passable.

Below, another garden corner.

The parish room of St Paul’s, also 1888.

And here, a view nearby, of Little Campden House.

This view says “down Hornton Place” (Hornton Place runs west off Hornton Street)

I’m not sure if the church tower would look quite so imposing in real life. (Although the modern surrounding buildings may be bigger now, and they didn’t have Google Street View in the 1880s.)

[Update a couple of weeks later: I went and stood at the end of Hornton Place, and the church tower does do some serious looming from thtt angle, so apologies to Elizabeth]

This picture, looking down Gordon Place (off Holland Street) is immediately recognizeable, even if the background has changed a little.

A small carriage trundles down another quiet road, Sheffield Terrace in this picture.

Once again, Elizabeth shows us solitary dwellings set amongst big trees, sitting behind low walls with a street so quiet a couple of birds can stand around in the middle once the carriage has passed by.

Now we actually move south of Kensington High Street,

Kensington Square, 1894 featuring another convent and a grammar school.

Below, the stables at Kensington Palace, a suitable spot for a painter to set up.

The lady in blue is competently done.

Unfortunately, the figure in the picture below (which I like, don’t get me wrong) in Dukes Lane walking opposite the walls of the Carmelite Monastery, really gets away from the artist.

Something wrong with the scale? (And the face?). Well, sorry Elizabeth, you can’t nail them all.

Postscript

Thanks to everyone who left a comment last week, especially those who corrected the identification of the streets. Unlike the Photo Survey pictures by John Rogers (who never made any errors in place names) those pictures may have been captioned (and dated) quite a while after the pictures wete taken. And the pictures didn’t originate with Local Studies. I was glad to have them uncovered after years of being lost. Actual lost pictures are actually quite rare – sometimes I come across images I’ve never seen before but it’s rare to find pictures that not even my predessessors knew about.