Lionel Davidson was a famous writer in his day, although not much mentioned these days. Many of his books are still in print though. He was big in the 60s. He wrote what you might call international thrillers -The Night of Wenceslas (1960) set in cold war Czechoslovakia, The Rose of Tibet (1962) set in India and Tibet and A long way to Shiloh (1966) set in Israel and Jordan. They were all bestsellers. The paperbacks were published by Penguin which made them look serious, like Len Deighton novels. (People sometimes forget now how innovative and influential Deighton was with books such as the Ipcress File and Billion Dollar Brain). Davidson himself is a literary ancestor of the modern authors of spy novels and techo-thrillers.

The covers of his books from the 60s and 70s tell their own story:

In the centre a classic Penguin crime cover – green for crime. On the left a later Penguin edition typical of the early 70s – the arty but somewhat gratuitous notion of a map projected on a naked body was used on a series of Davidson novels. On the right the semi-surreal hardback cover for the Sun Chemist also typical of books from Jonathan Cape

In 1978 Cape published another Davidson crime thriller (with a tasteful cover ) in another exotic setting – The Chelsea Murders.

The novel begins with a lone woman who is surprised by a grotesquely masked man and killed. But she is not the first victim.

Previously another woman was murdered in Jubilee Place, and a man in Bywater Street.

The police begin to wonder if a maniac is killing people in Chelsea.

I have read that Davidson never visited Chelsea before writing the book and employed researchers to get the local colour. He lived in Israel by this time so his own knowledge of London may be a little out of date – for example there’s no mention in the book of the punk scene which would have been well established by 1978.

There are some scenes set in Chelsea Library. In the book it’s the reference library at the old Chelsea Library in Manresa Road (well before my time although I have been in the old reference libary with its dark curving shelves and balcony). Here it is in a picture from the 50s 0r early 60s:

Several characters visit the library where Brenda the library assistant supplies information about famous local residents to a police detective. Mason notices her shelving – “Very nice bird,(he) thought. Victorian looking, yellow hair, parted in the middle; something a bit classical happened to it at the back.” Artie Johnson who will become one of the suspects notices Brenda in the first few pages of the and notes that she had “the look of a Pre-Raphaelite chick.”

Unfortunately for the police Brenda also tells Mary Mooney, an ambitious young reporter following the case (and are there any other kinds of journalists in thrillers?), and some of the suspects. One of those two women ends up in the killer’s sights but I won’t give away which one.

The exterior of the 1890s building, which you can still see today in Manresa Road:

When ITV did an adaptation of the book, those scenes were filmed in the new Chelsea Library at Chelsea Old Town Hall. I was already working for the Libraries then, and several years later I was reference librarian there, so whatever Davidson’s personal experience of Chelsea was, I feel like this is a book set more or less in my own habitat.

There are some characters familiar from the 60s and 70s:

A group of former art students who are making a film. Two of them and their mentor, a sleazy academic become the main suspects in the series of murders in which it seems that the killer is choosing his victims by their initials which match the names of some of those famous residents.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, (hence the painting on the cover of the book) is the first of the series which also features James McNeill Whistler, Algernon Swinburne, Leigh Hunt, AA Milne, W S Gilbert and even Oscar Wilde.

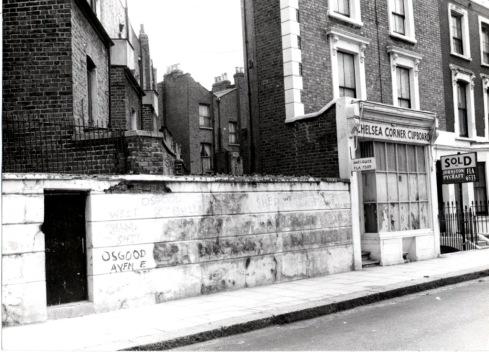

DGR was a woman murdered and dumped in the river. Ogden Wu, the owner of a slightly seedy shop selling denim in all its forms like in this market off the King’s Road is one of the later victims:

One of the desperate film makers works for Wu and finds himself even more deeply embroiled in the investigation after his boss’s death.

The police fixate on the suspects fairly early on. They trail them around, create a card index for the case (no mention of a computer in the book), even consult a reference book at the library to trace the provenance of a poem.

As you might expect they spend some time in one of the famous Chelsea pubs of thr era.

Some of the language in the book has dated in a way which modern readers might find distasteful. The character Artie Johnson, the producer of the film is described (by a tabloid journalist ) as “a spade..a real one, all black” and Mooney thinks of him as “a long black cat, his golliwog smile in place under his beehive” (afro, presumably). That’s a phrase you couldn’t use (and wouldn’t want to) these days, but in 1978 casual racism was still prevalent in life as well as literature. The author was not of course necessarily endorsing the attitudes of his characters. Thrillers from previous eras exhibit many archaic attutudes whether it’s the off putting right wing opinions of Dennis Wheatley or the less offensive 1930s mannerisms of Michael Innes. The modern reader has to tread carefully when reading and the modern blogger when recommending books.

In fact I’m not sure whether I’d actually recommend the Chelsea Murders to anyone who wasn’t interested in the Chelsea setting. The local colour is the thing. It’s not quite the 1978 I remember, but then Chelsea in those days probably still contained pockets of previous eras.

Also, the serial killer genre has moved on since 1978 for better or worse. Davidson’s book is also a traditional whodunnit and the two genres don’t work very well together. The motivation of the killer is rather perfunctory and you get the impression that he is simply play acting.

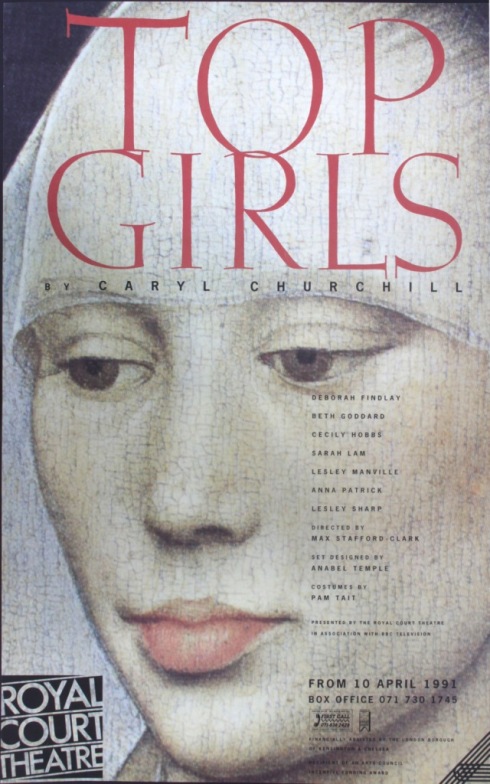

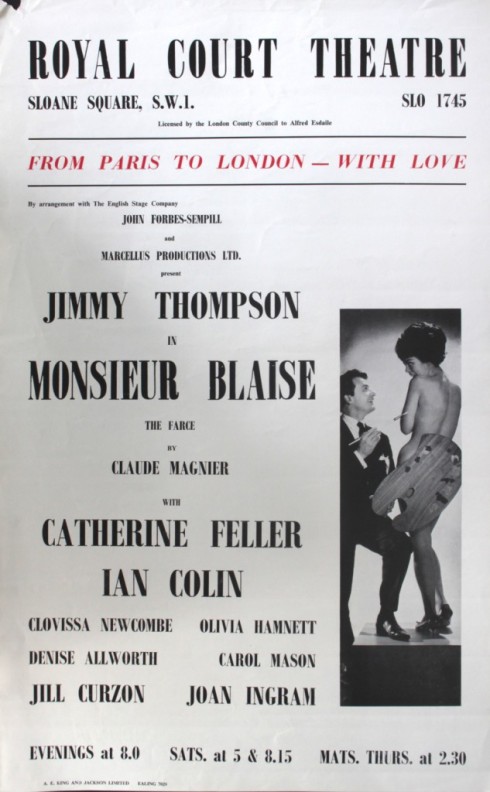

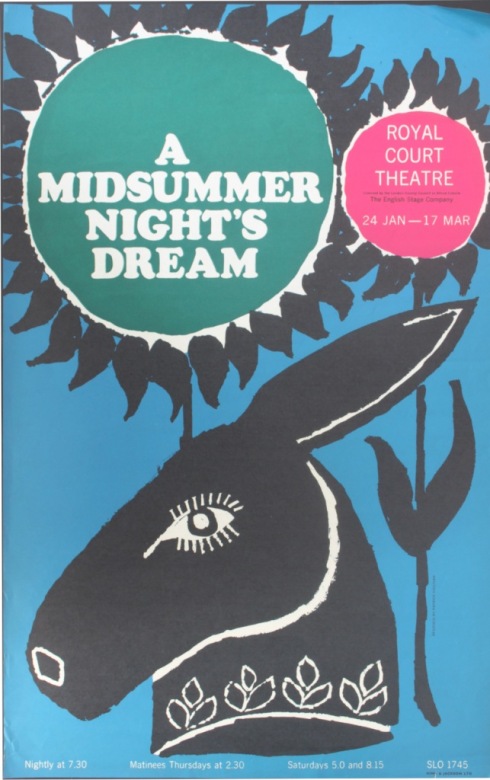

Although, like the Chelsea Murders, that can sometimes be effective:

And there is a decent twist at the end.

Postscript

The last picture is unmistakeably one of John Bignell’s arty but playful images, called Satan triumphant (1958). As with many of his pictures there’s no hint as to why it was taken. Some of the other pictures in this post are also by Bignell.

I’ve been tinkering with this post for weeks and reading the book in installments (I hate being obliged to read a book even when it was my own idea) so I’m glad to finally put it to bed. I hope it was worth the effort.